Dec 4, 2025·Special Population & Related Conditions

Child Giftedness

Is the gifted test an IQ test? Often yes—most gifted programs use real IQ tests (like WISC or CogAT) or closely related cognitive ability tests to identify high-intelligence kids. Discover exactly how schools test for giftedness.

Gifted education has been a topic of fascination, debate, and sometimes controversy for over a century. Parents want to know if their child is gifted, schools struggle with how to identify and serve gifted students, and researchers argue about who is (and who is not) gifted.

The term "gifted" lacks a single, universally accepted definition. Different states, school districts, and experts define it differently. This inconsistency creates confusion, but understanding the concept still has practical value for parents and educators.

Who Is Gifted?

In the early 20th century, psychologists equated giftedness with high IQ. Lewis Terman launched a famous longitudinal study in the 1920s following children with IQs above 140. For decades, "gifted" simply meant "high IQ."

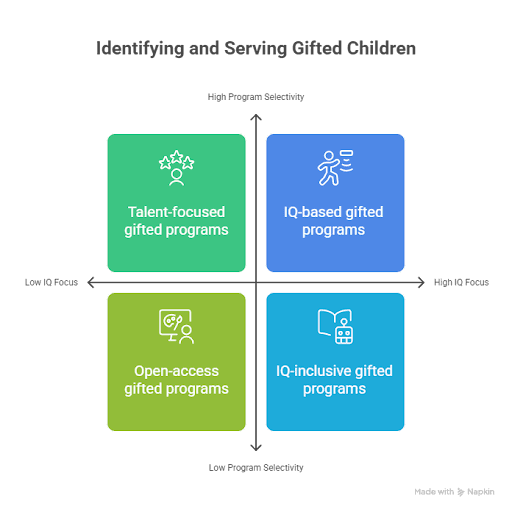

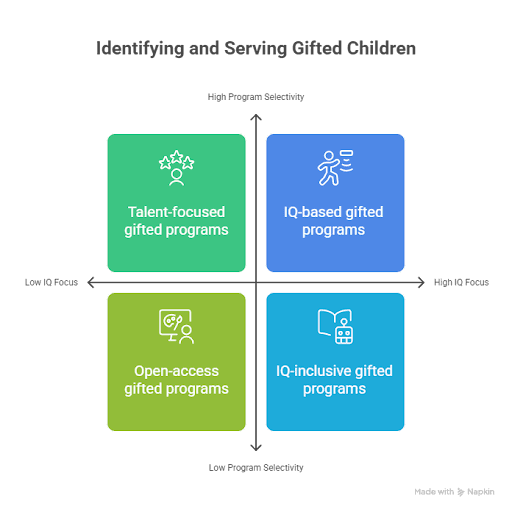

That view has expanded and fractured. Today, state definitions of giftedness vary wildly. Some states emphasize IQ. Others focus on specific talents in areas like leadership, creativity, or the arts. Some use multiple criteria, allowing children to qualify through different pathways.

This diversity has advantages and disadvantages. It broadens access to gifted programs and recognizes that exceptional ability takes many forms. But it also creates incoherence. When definitions are contradictory, making generalizations about "gifted children" becomes nearly impossible.

The Role of IQ in Identifying Giftedness

Despite the proliferation of definitions, cognitive abilities remain central to most conceptions of giftedness -- and general intelligence relates to every cognitive ability. Intelligence is one of the best-understood constructs in psychology, and IQ tests are among the most reliable and valid instruments available. This makes IQ a firmer foundation than alternatives like creativity assessments or teacher nominations, which tend to be less reliable.

That doesn't mean "gifted" equals "high IQ," but it does mean intelligence should be part of the conversation. Ignoring cognitive ability when discussing giftedness creates more problems than it solves.

When gifted programs do use IQ cutoffs, the threshold is often somewhere between 120 and 130, depending on the program's selectivity and available resources. These thresholds are arbitrary. A child with an IQ of 129 is not meaningfully different from one with an IQ of 131, even though only the latter might qualify for services.

Identifying Gifted Children

Schools use various methods to identify gifted students:

IQ tests. Individual tests like the WISC or group tests like the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT) are common. These provide standardized, objective measures of cognitive ability.

Achievement tests. Standardized tests measuring what children have already learned in reading, math, and other subjects can identify high achievers. Many jurisdictions require these tests at the end of the school year at many grade levels already. So, this makes them a convenient tool for selecting students for gifted programs.

Teacher nominations. Teachers identify students who demonstrate exceptional ability in the classroom. This method captures children who might not test well but show obvious talent. However, teacher nominations can be influenced by factors unrelated to ability, like behavior or socioeconomic status.

Portfolio reviews. Some programs evaluate student work samples, projects, or performances.

Parent nominations. Parents often notice their child's abilities early, before formal identification occurs.

Many programs use multiple criteria, requiring children to meet thresholds on several measures rather than just one. This reduces the risk of misidentification but can also exclude genuinely gifted children who have uneven profiles or don't perform well in testing situations. Other programs avoid this problem by allowing a high score in one area to compensate for a low score in another. Another option is to have multiple criteria and only require a child to exceed the cutoff in one area in order to be admitted. Each of these strategies has advantages and drawbacks.

Characteristics of Gifted Children

What are gifted children like? Decades of research provide some answers, though individual variation is enormous.

Intellectually gifted children typically learn quickly, grasp complex ideas earlier than age-peers, have strong memories, and show intense curiosity. They often ask probing questions, see connections others miss, and prefer challenging material to repetitive practice.

Socially and emotionally, the picture is more complicated. An old stereotype suggests that gifted children are maladjusted, as in the "mad genius" or socially awkward prodigy. This stereotype is largely false. Terman's longitudinal study found that gifted children grew into well-adjusted adults with lower rates of criminality and higher rates of success than the general population.

Modern research confirms this pattern. Gifted children generally have better mental health, not worse. High IQ correlates with positive outcomes across many domains: academic achievement, occupational success, physical health, and longevity.

There are exceptions. Some conditions, like high-functioning autism and anorexia, are more common in high-IQ individuals. But the general pattern contradicts the stereotype of the troubled genius.

Some gifted education advocates claim that gifted children have unique psychological experiences, like more intense emotions, deeper empathy, or heightened sensitivity to injustice. These claims lack empirical support. Gifted children aren't emotionally different from other children; they're just better at solving problems and learning quickly.

Do Gifted Children Need Special Services?

Yes, for several reasons.

Academic pacing. Gifted children learn faster than typical curricula move. When forced to learn at the pace designed for average students, many become bored, disengaged, or develop poor study habits because nothing challenges them.

Appropriate challenge. Like all children, gifted students need to work at the edge of their abilities to develop persistence, problem-solving skills, and resilience. If everything comes easily, they never learn to struggle productively.

Depth and complexity. Gifted learners benefit from going deeper into subjects rather than just moving faster through standard material. They can handle abstract concepts, multiple perspectives, and ambiguity earlier than age-peers.

Social and emotional needs. While gifted children aren't more emotionally fragile, they do benefit from having peers who can engage with them intellectually. Profound ability differences can make friendships difficult when interests and conversation levels don't align.

Schools address these needs through various approaches: pull-out programs, self-contained gifted classrooms, acceleration, enrichment, differentiated instruction within regular classrooms, or combinations of these strategies. No single approach works for all gifted students.

Acceleration vs. Enrichment

Two main strategies serve gifted students: acceleration and enrichment.

Acceleration means moving through content faster through grade skipping, subject acceleration (taking algebra in 6th grade, for example), or early college admission. Research consistently shows that appropriate acceleration benefits gifted students academically and socially, despite concerns about social adjustment.

Enrichment provides broader, deeper learning experiences without necessarily moving to higher grade-level content. This might include independent projects, philosophical discussions, creative problem-solving, or exposure to topics not in the standard curriculum.

Both approaches have value. The best choice depends on the individual child's needs, strengths, and circumstances.

Equity and Access

Gifted education faces persistent equity problems. Children from low-income families, racial minorities, and English language learners are underrepresented in gifted programs. Multiple factors contribute to this:

• Unequal access to early learning opportunities affects test performance

• Teacher nominations reflect unconscious biases

• Families differ in advocacy and awareness of gifted services

• Some identification methods favor children from educated families

• High ability may not be equally distributed across all groups

These disparities don't mean IQ tests are biased. Professionally developed tests undergo extensive bias screening and are often the least biased part of the selection process for a gifted program. But identification systems as a whole can be biased.

Addressing these equity issues requires multiple strategies: universal screening (testing all children rather than only nominated ones), recognizing different pathways to demonstrating ability, providing test preparation to level the playing field, and actively recruiting underrepresented students. However, admissions standards should never be lowered so that a gifted program can have the “right” demographic balance. Doing so will water down the gifted program so that it does not serve its originally intended student population well. It may also be discriminatory for children who are held to a higher admissions standard and may leave a school district open to a lawsuit.

Is Giftedness Fixed?

Intelligence is relatively stable over time, but environmental factors matter. Education raises IQ by roughly 1-2 points per year. Stimulating environments, access to books and educational resources, and cultural emphasis on learning all influence cognitive development. However, the importance of environmental effects fade with time. Best practice is to re-evaluate younger children regularly so that home environment advantages do not play an outsized role in participation in gifted programs.

As children age and their cognitive abilities stabilize, children with above-average aptitudes and higher intelligence will likely remain above average throughout life. But whether they maintain exceptional performance depends partly on continued challenge, support, and opportunity.

The Bottom Line

Qualification for gifted programs typically involves high intelligence, though definitions vary across settings. Intellectually gifted children learn faster, grasp complex ideas earlier, and need appropriate challenges to develop their potential.

Identifying and serving gifted students matters. These children deserve educational opportunities matched to their abilities, just as children with learning disabilities deserve appropriate support. Gifted education is not elitist, but rather a consequence recognizing that children develop at different rates and need differentiated instruction.

The goal isn't to label children as "better" than others, but to ensure all students -- including those at the high end of ability -- receive education suited to their needs. When gifted children are appropriately challenged, everyone benefits: the students themselves and society as a whole.

Article Categories

All ArticlesUnderstanding IQ ScoresTaking an IQ TestRIOT-Specific InformationGeneral IQ & IntelligenceAdvanced Topics & ResearchIQ Scores & InterpretationMensa & High-IQ SocietiesOnline IQ Tests IQ Test Basics & FundamentalsAverage IQ & DemographicsFamous People & IQHistory & Origins Of IQ TestingAccuracy, Reliability & CriticismSpecial Population & Related ConditionsImproving IQ / PreparationSpecific IQ Tests & FormatsIQ Testing for HR & RecruitmentSkills Assessment

Related Articles

Take our IQ testsCompare all tests

Basic IQ Test

5 subtests + 5 cognitive abilities

Features

- ~13 Minutes

- IQ score

- Cognitive abilities breakdown

- ±5.6 IQ margin of error

5/15 Subtests

Learn moreVocabulary

Matrix Reasoning

SToVeS

Visual Reversal

Symbol Search

Full IQ Test

15 subtests + all cognitive abilities

Features

- ~52 Minutes

- IQ score

- Cognitive abilities breakdown

- ±3.7 IQ margin of error

15/15 Subtests

Learn moreVocabulary, Information, Analogies

Matrix Reasoning, Visual Puzzles, Figure Weights

Object Rotation, SToVeS, Spatial Orientation

Computation Span, Exposure Memory, Visual Reversal

Symbol Search, Abstract Matching

Simple Reaction Time, Choice Reaction Time

Community

Intelligence Journals & Organizations

News & Press

Our Articles

Our Articles

Our Articles

Our Articles

Our Articles